Digital Transition: The Opportunity in Data Center REITs & Digital Infrastructure

Data Centres & Cellular Towers: The Backbone of Our Digital World

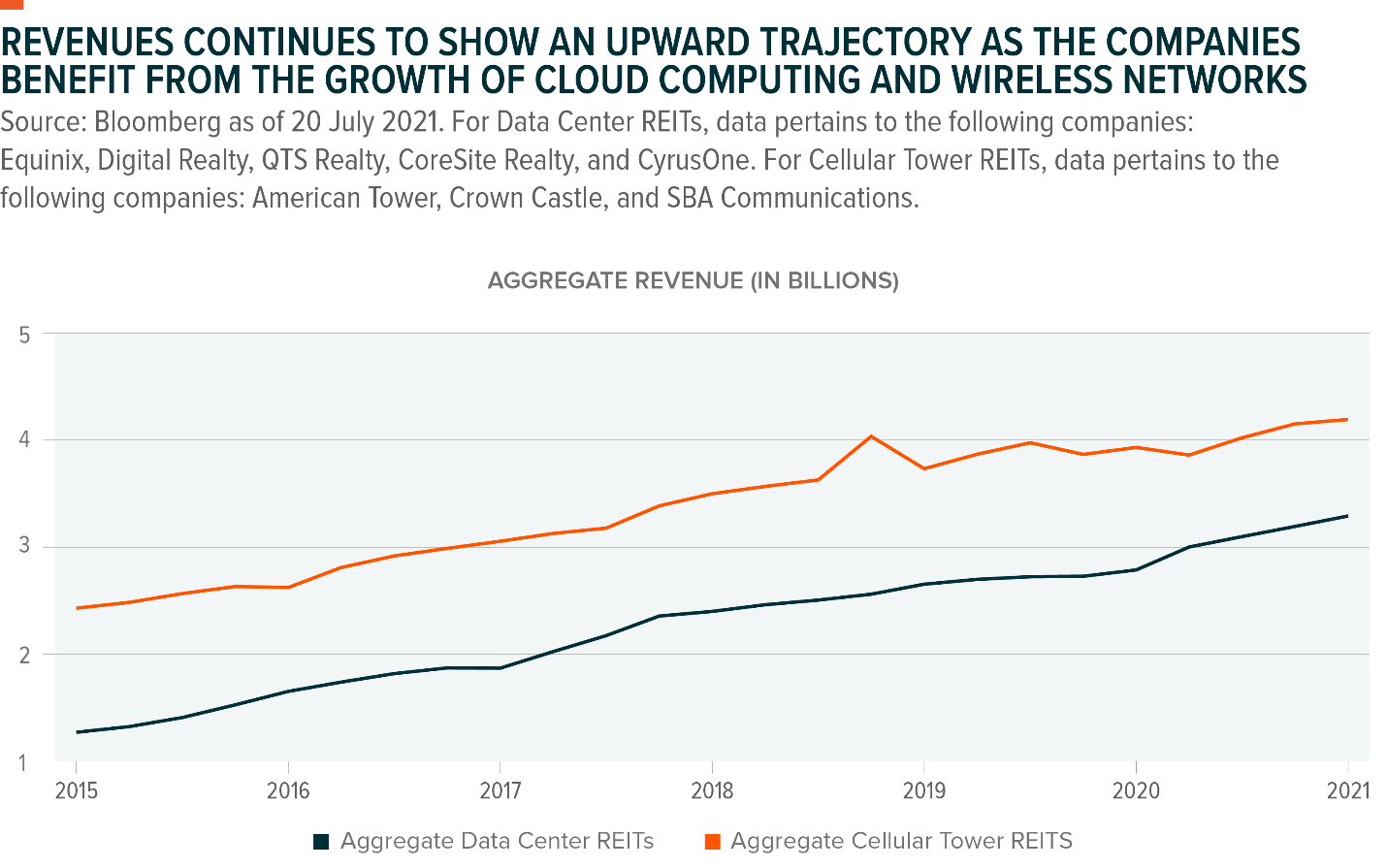

A confluence of multiple digital technologies is expected to define this decade: billions of internet connected devices will transmit zettabytes of data across blazing fast 5G networks, which will be stored or analysed in the cloud by sophisticated artificial intelligence algorithms.

As much as these technologies appear to occur effortlessly and out of thin air, they require an extensive network of physical infrastructure and hardware. Cellular towers transmit and receive radio signals to wireless devices, while data centres host servers that store and process information. Together, they form the backbone of the digital and wireless technologies that we use daily.

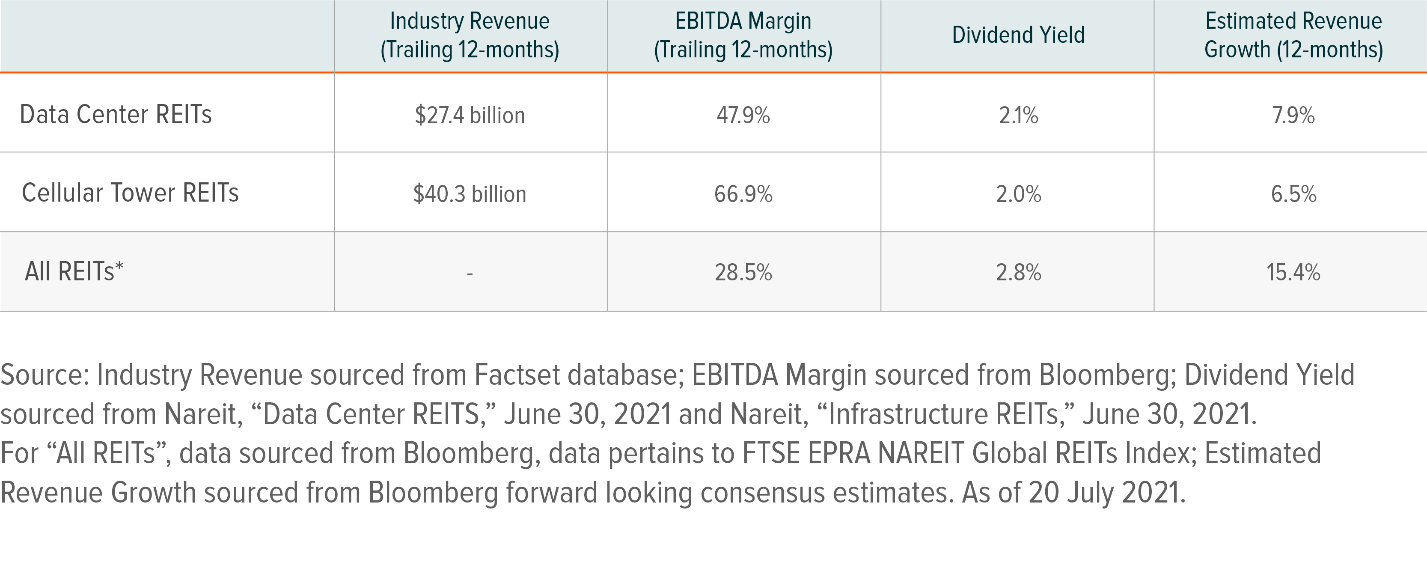

For investors, data centres and cellular towers marry elements of growth-oriented technology investing, with income-oriented real estate. As disruptive technologies like the Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence, and Video Games & Esports require vast amounts of data storage and processing, demand for data centres and cell towers could continue to surge, along with hardware that powers these structures. Yet many of these companies operate as real estate investment trusts (REITs), distributing at least 90% of their taxable income to shareholders as dividends. With interest rates at record lows and stalling global economic growth, data centres and cell towers could offer attractive growth and income characteristics to investors’ portfolios.

Data Centres: The Cloud is on the Ground

Data centres are traditionally large, windowless, warehouse-like buildings that host their tenant’s networked computer servers. In exchange for regular rent payments and fees, data centres provide physical space, cooling, power management, and security to their tenants, but rarely own or operate their own servers. Unlike other REITs, data centre leases are primarily based on power capacity usage ($/kW) rather than square footage. This business model gives tenants significant flexibility to scale their infrastructure and computing needs.

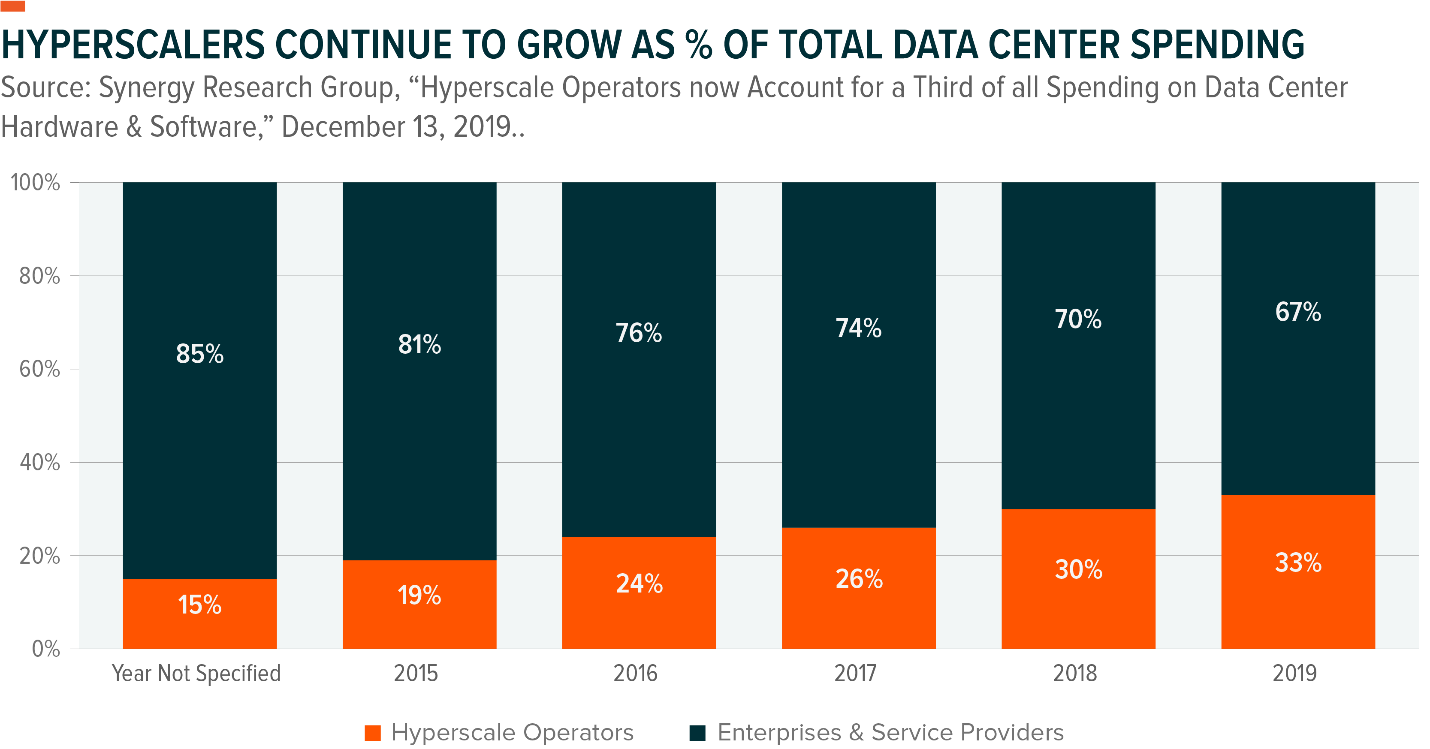

With widespread digitalisation across the economy, a data centre’s tenants can range from big tech companies, to government agencies, financial services firms, or health care providers. A large and growing share of data centre revenue comes from leasing to hyperscalers like Google, Amazon, Facebook, IBM, Alibaba, Oracle and Microsoft. While these companies often directly own and operate their own data centres, they also lease facilities from data centre providers such as Equinix, Digital Realty, CyrusOne, CoreSite Realty, QTS Realty, Switch, GDS Holdings, NextDC, KeppelDC, 21Vianet Group, and SUNeVision Holdings.

Like much of the real estate world, the physical location of a data centre plays an important role in its ability to command premium rents. First, approximately 20% of the data centre costs come from power usage, a cost that is typically passed on to tenants. Therefore, locating a data centre in an area that offers low energy costs can be attractive to customers. Second, the proximity of data centres to populous areas can greatly reduce latency, or the time it takes for information to travel to and from the data centre – a feature that is particularly important for disruptive technologies like online gaming and remote surgery. Third, access to multiple internet service providers (ISPs) and interconnection across multiple tenants can play an important role as well, creating a ‘network effect’ within the data centre itself. Given that it can take years to permit, build, and lease a new data centre, existing properties in attractive locations can command high rents, and competition is somewhat limited. In addition, high switching costs associated with moving, re-installing, and testing servers in a new location means lease renewal rates are quite high.

Wholesale vs. Retail Data Centres

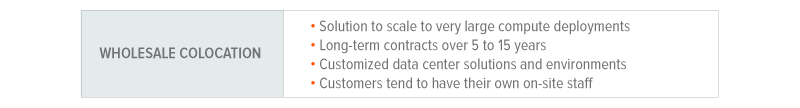

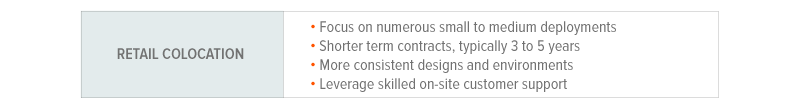

Data centre operators primarily focus on either wholesale or retail offerings.

Wholesale: Wholesale data centre providers offer limited services – space, cooling, security, and power – to sophisticated tenants that manage their own networking equipment, either for their own uses or to sub-lease to their own customers. Wholesale contracts tend to be longer term (often 5 to 15 years) and include built in fee escalators and options for renewal.1

Retail Colocation: Retail data centre operators focus on leasing to numerous smaller and less sophisticated clients. These providers offer more built-out solutions, including racks, cages, and cabling, and typically offer shorter term contracts in the range of 3 to 5 years.2 A single retail operator may have dozens of clients in a single data centre.

Cellular Towers: Wireless Highways

Similar to data centres, cellular towers own and operate critical physical infrastructure for the digital world, including wireless and broadcast communications towers. In the U.S., cell towers lease vertical space on the tower and land underneath primarily to major telecom providers like AT&T, Verizon, the T-Mobile/Sprint merged entity, and, more recently, Dish Network.3

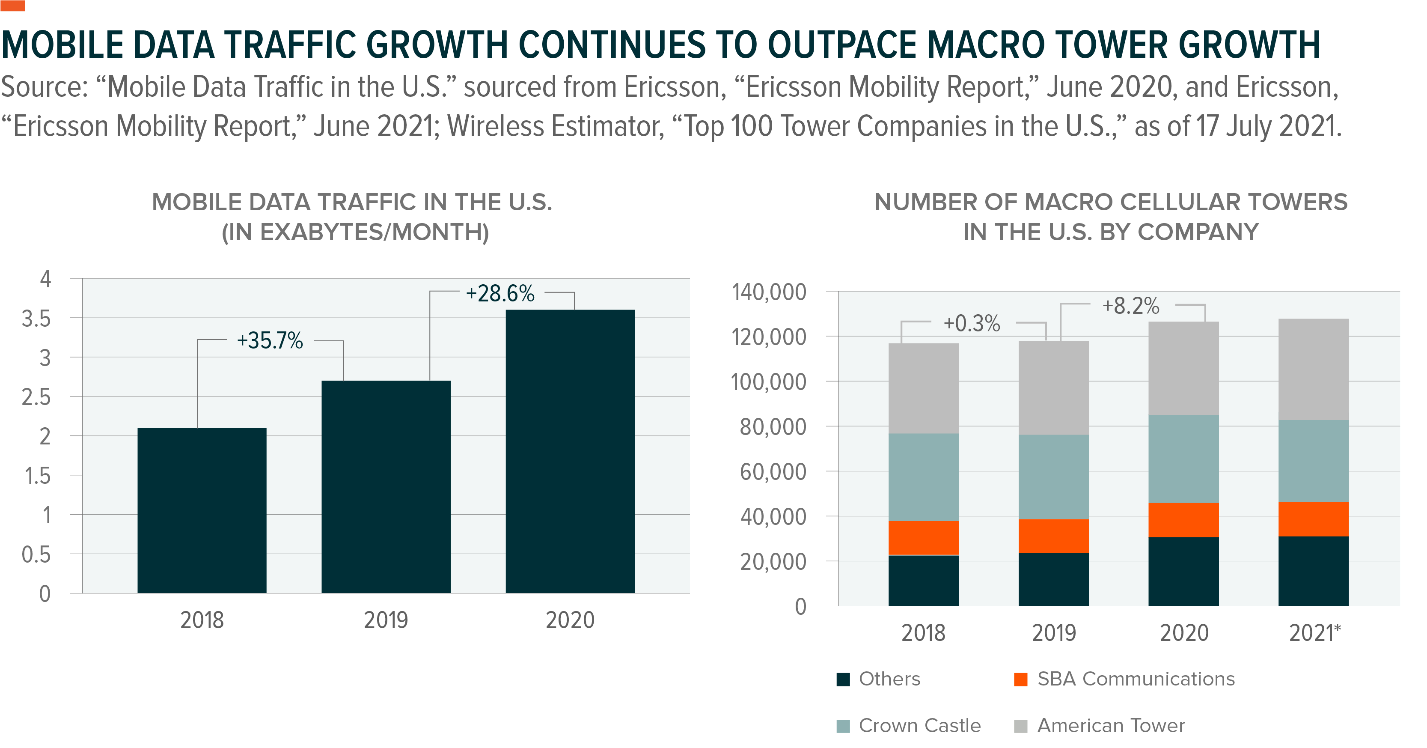

Even though the number of potential customers is limited to a handful of telecoms, the need for towers is greater than ever with the rapid accent of smart phones and the internet of things. Today, there are approximately 128,000 macro cell towers in the U.S., but each tower only has so much range and capacity. A typical cell phone has only enough power to reach a tower up to 5-7 miles away, and a single LTE cell can only manage around 200 connections per 5MHz of spectrum before speed begins to stall.4,5 With 3.2 billion active smartphone users globally – and counting – tower demand is expected to remain robust.6 But construction and permitting hurdles often limit expansion, making existing towers increasingly valuable. For example, suppliers of macro cell towers in the US added approximately 8% tower capacity from 2019 to 2020.7 But that lags substantially behind the 29% growth of mobile data per smartphone in North America.8

Given that wireless towers face data and capacity constraints, tower operators are increasingly developing small cell networks or small low-powered-antennas (nodes) to alleviate congestion. Small cells are often attached to utility poles or streetlights and connected to fibre optic cables to enhance connectivity in densely populated areas.9 Some estimates expect small cells in the U.S. to grow eight-fold from about 100,000 in 2020 to 800,000 by 2026 as new technologies like 5G and autonomous vehicles rapidly accelerate data demands.10,11

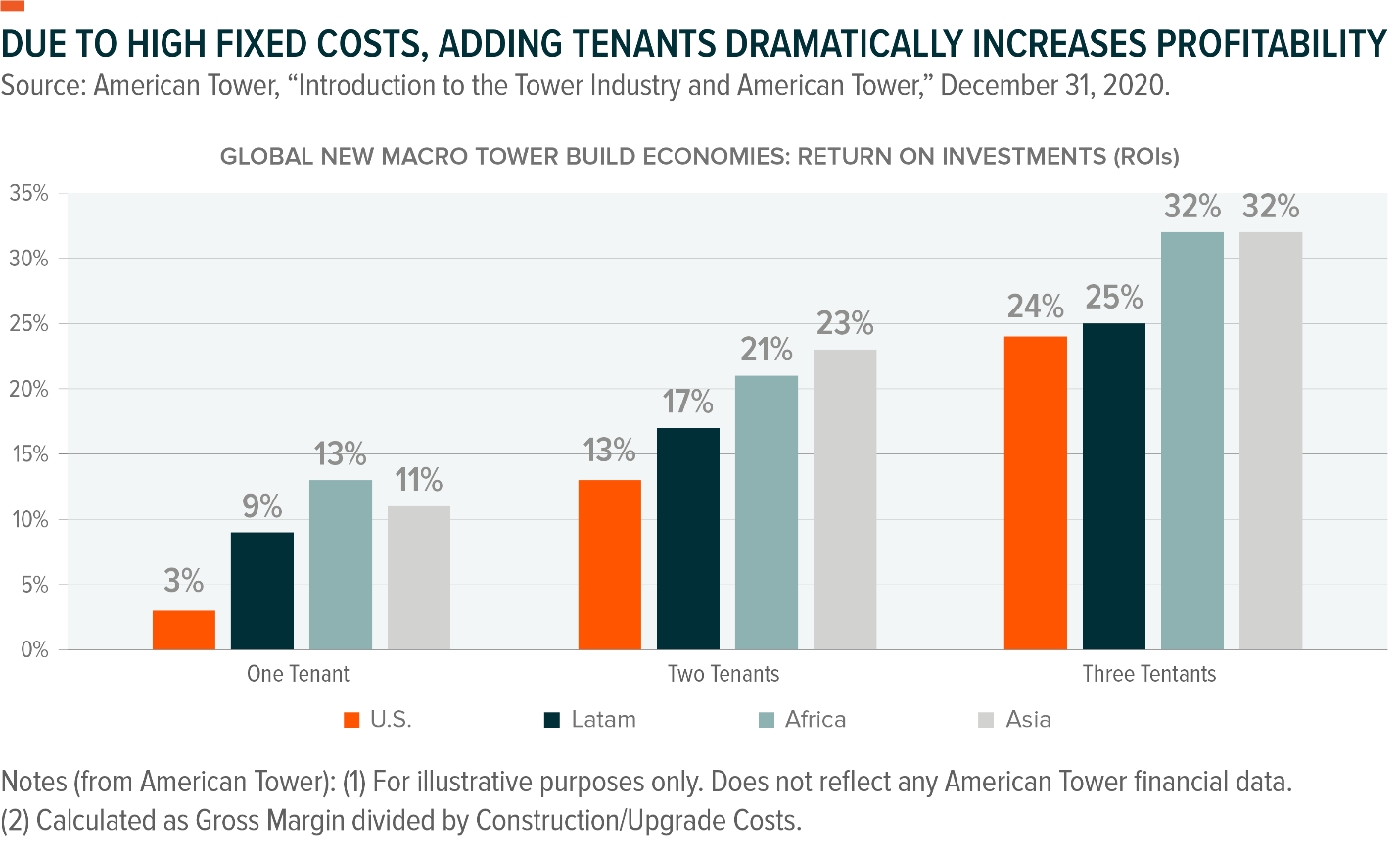

Tower rents vary by property location, leased vertical square footage on the tower, and the weight on tower. Cell tower leases generally range from 5–10 years.12 Importantly, most contracts are non-cancellable and have escalators that increase lease payment by approximately 3% annually.13 Largely fixed operating costs support these long-term contracts. Most costs come from monitoring the tower, insurance, taxes, utilities, maintenance. In some cases, ground rent is a cost, depending on whether the tower provider owns or rents the land beneath the tower. But these costs tend to be fixed whether a tower has one tenant or five – so as the number of tenants increases, revenue grows, but costs remain relatively flat. A single cell tower often hosts four or five telecom tenants, so the multi-tenant structure helps diversify long-term revenue streams and increases profitability.

Digital Infrastructure Hardware: Powering the Shift to Digitalisation

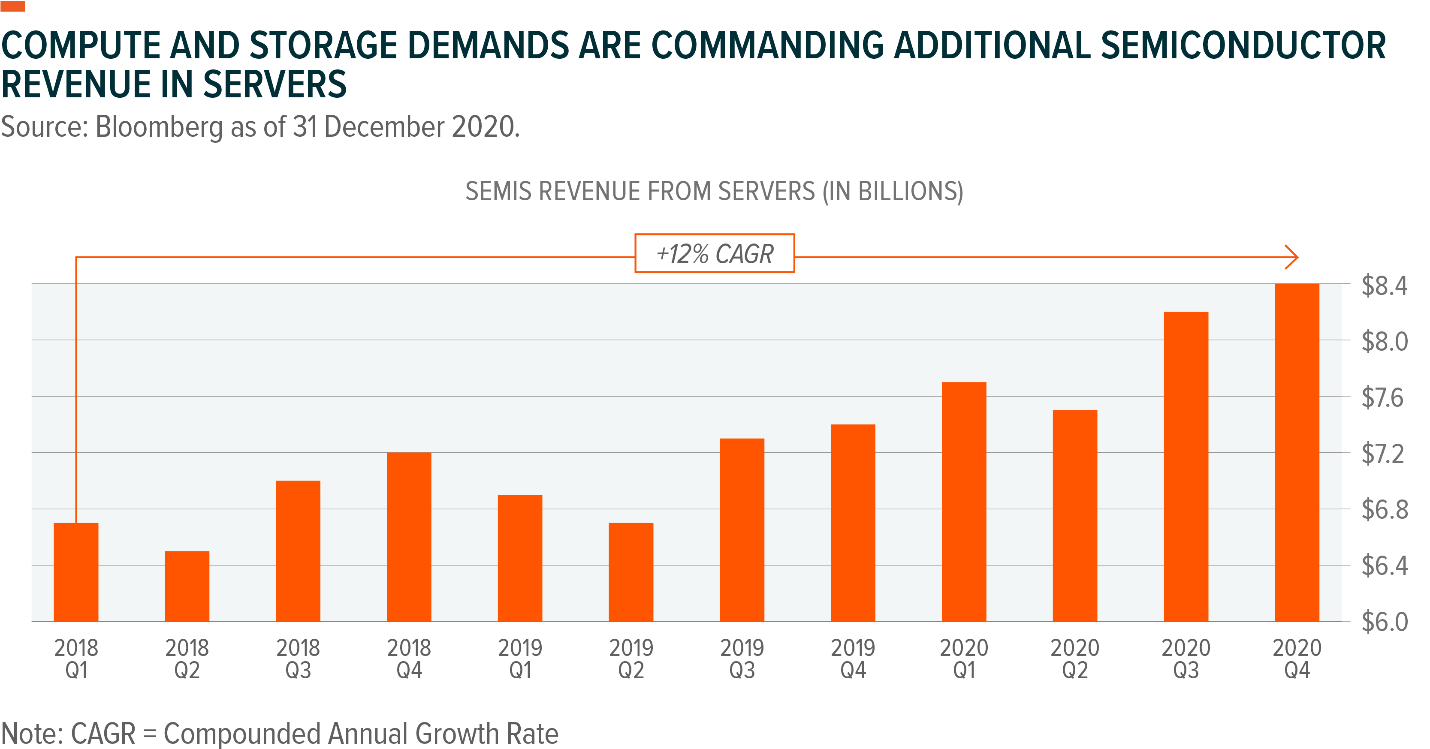

The world’s growing reliance on connectivity and cloud computing makes digital infrastructure more important than ever. Memory and processing power are fundamental pillars of this ecosystem, so as demand for data centres grows, so too should demand for the hardware that goes inside them. In fact, semiconductor revenue within the server segment grew by approximately 12% annually since 2018.14

For decades, servers were powered by central processing units (CPUs) that efficiently computed single threads of information. But with data centres expected to handle complex AI algorithms or billions of daily internet queries, processors are evolving. In recent years, graphic processing units (GPUs) became the state of the art hardware due to their ability to process multiple computations simultaneously.15 In the future, data-centric designs, known as data processing units (DPUs), could be the next generation of computational chips. DPUs enable a variety of data centre solutions, including storing, computing, and data security at the highest speeds while lowering cost and time by analysing data at the edge.16

As you can tell from the description above, data centre hardware ages quickly as computing requirements evolve. Amazon, for example, estimates a 4-year useful life for their AWS servers.17 A hyperscale data centre holds at least 5,000 servers, and can often reach hundreds of thousands of servers, representing tens of millions of dollars in IT hardware. Therefore, the strong demand for data centre hardware stems from both the addition of new data centres around the world, as well as the ongoing maintenance and upgrades within existing data centres to support the latest technologies.

Digital Infrastructure: Real Estate with Income & Growth Potential

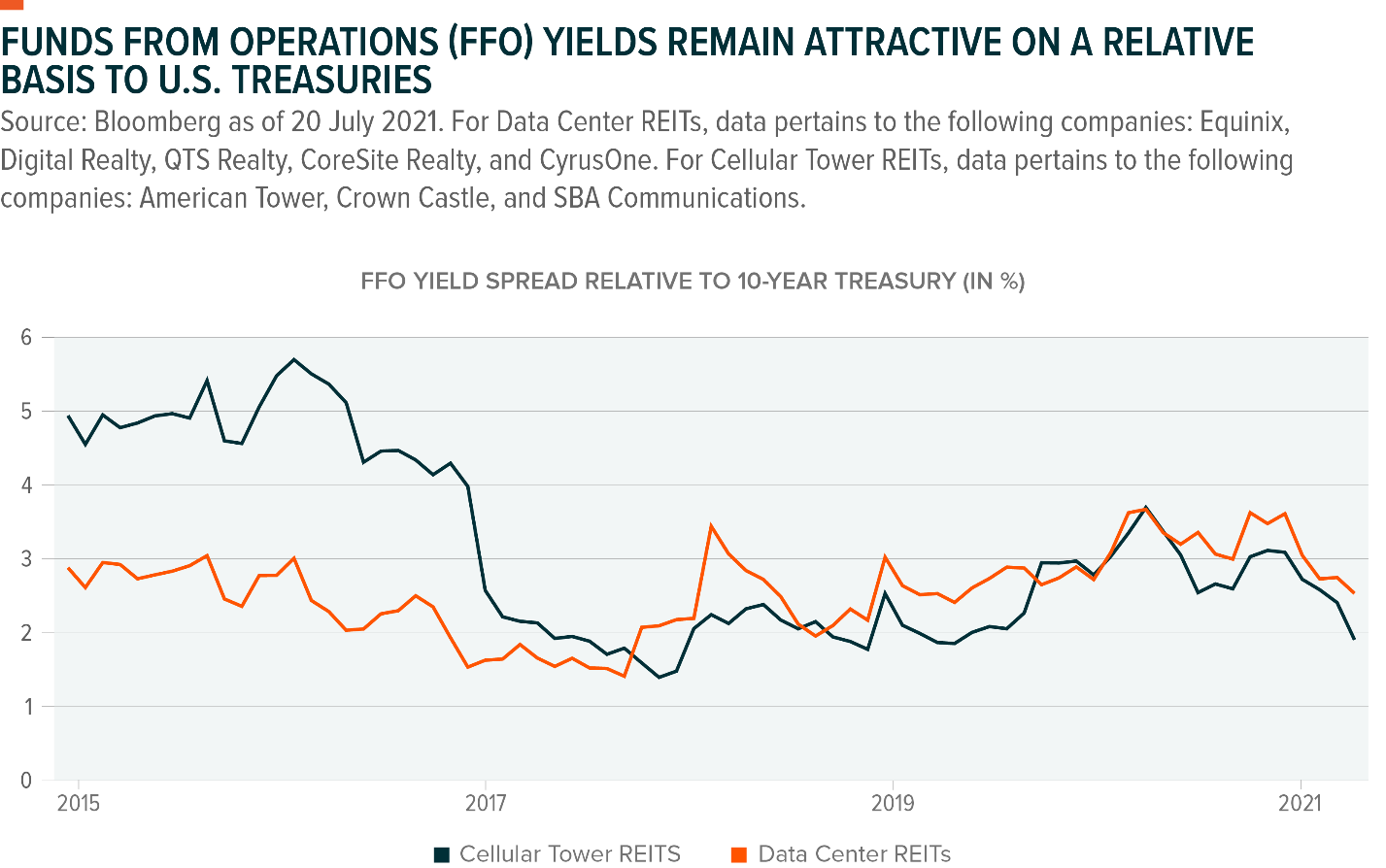

From a portfolio perspective, digital infrastructure can offer compelling growth and income characteristics amid the current environment. With interest rates near zero in most major developed economies and a stalling macroeconomic backdrop, investors are increasingly looking for alternatives to fixed income that can provide meaningful yield and upside opportunity.

The spread between the Fund from Operations (FFO) yield for data centres and cellular towers versus the 10-year US Treasury has generally increased over the last three years to approximately 300 basis points. FFO offers a better way to determine a real estate investment’s operating cash flow than earnings because depreciation and amortisation (non-cash expenses) are deducted from net income. A rising spread versus 10-year US Treasuries can indicate that digital infrastructure is exhibiting improving valuations.

Beyond income, digital infrastructure could continue to experience strong growth as it is well-positioned to benefit from the changing economic landscape. Traditional real estate segments such as shopping malls, offices, and apartment buildings face secular disruptions from emerging technologies and new consumer behaviours. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers are increasingly opting to shop online, work from home, and socialise via video and gaming apps. These changing patterns are shifting real estate demand from large public areas and towards our private residences. Occurring in parallel with this shift is increasing demand for the digital infrastructure that powers this remote connectivity.

Digital infrastructure sits at the intersection of numerous disruptive trends, from increasing connectivity through the growth of 5G and the internet of things, to the rise of big data and artificial intelligence, and the transition to software delivered seamlessly through the cloud. We believe that such infrastructure is therefore essential to 21st century growth and can play a multi-faceted role in investors’ portfolios that could offer income and growth characteristics.

This document is not intended to be, or does not constitute, investment research