Sustainable Transition: The Opportunity in U.S. Infrastructure Development

Infrastructure is a key component of the US economy: it provides jobs, it facilitates commerce, and it includes cities, towns, roads, bridges, ports, and airports. The global pandemic and new potential public sector spending initiatives will continue impacting most facets of life in the US for the foreseeable future.1 Infrastructure is no exception. The need to rebuild America’s infrastructure is still as acute as ever, but with new government leadership, low interest rates, and the dark cloud of the pandemic remaining, the way we build may differ.

How Important Is Infrastructure to Economic Growth?

Infrastructure includes highways, streets, rail, transit, airports, seaports, waterways, waste management, power grids, communications equipment, and pipelines. Infrastructure is the backbone to any economy as it facilitates the movement of goods and labour, which allows for greater competition, higher productivity, and reduced costs. Therefore, many economists believe that increases in public or private spending on infrastructure development can significantly boost economic growth. According to research from S&P, a 1% increase in US infrastructure spending as a percentage of GDP translates to a 1.7% increase in GDP over the next three years, or a 70% return on investment.2

What Is the Current State of the US’s Infrastructure?

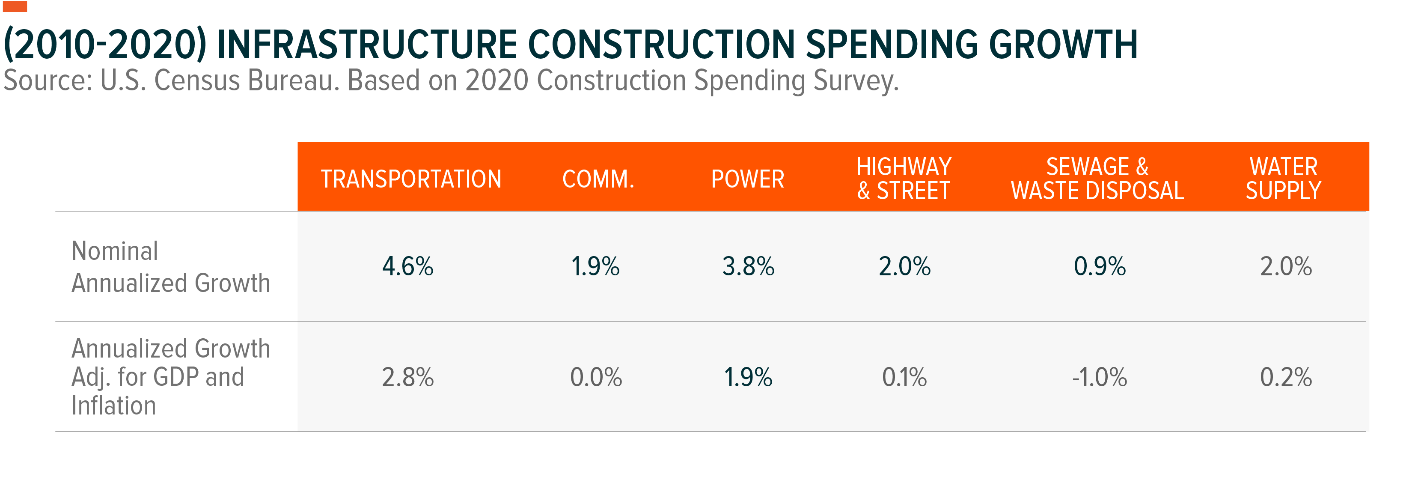

The US’s infrastructure, which was largely built in the post-WWII period of the 20th century, is rapidly aging, while suffering from a shortage of funding required to maintain these assets. While spending on infrastructure construction has nominally increased at an annualised rate of 2.5% over the last ten years, it has actually increased at an annualised rate of 0.7% once controlling for inflation.3 These numbers tell an even more troubling story when broken into various segments of infrastructure. In the chart below, note that the Transportation and Power segments are the only category demonstrating a significant real construction spending growth over the period.

As a result of this low level of investment in infrastructure maintenance and development, the US’s infrastructure assets are deteriorating and in dire need of repair: The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave America’s infrastructure a C- on its 2021 ‘Report Card’, noting that neglecting infrastructure can have severe negative economic consequences for the country. ASCE believes that America’s infrastructure spending gap could reach US$5.6 trillion by 2039, and that this gap, if unaddressed, could lead to the loss of three million jobs between now and then.4 Continued underinvestment over this period could cost the United States US$10 trillion in GDP and US$2.4 trillion in exports.5

ASCE analysis indicates that current levels of funding will be available to cover only 57% (approximately US$3.5 trillion) of these needs through 2029, and 56.6% (US$7.3 trillion) by 2039 for the aggregate of surface transportation, water transportation, airports, water, wastewater, and electricity systems.

How Will the Pandemic Change Infrastructure Plans?

The longstanding structural trend of urbanisation is an important input for infrastructure development plans as more densely populated cities and expanding urban sprawls require accommodative physical structures. COVID-19 introduced a headwind to this trend. Faced with global stay-at-home and social distancing orders, many are evaluating whether urban living presents the same appeal as it once did. Though a pandemic-driven urban exodus didn’t occur en-masse, many of the US’ largest and densest cities like New York and San Francisco saw heightened migration during the pandemic. This does not mean that cities will cease to exist, but the distribution of populations across major cities, satellite cities, and suburban towns could evolve, placing different demands on physical and digital infrastructure:

- Coordinated stacks of shoebox apartments and offices seem less viable in a post-pandemic world where proximity to others will be scrutinised. Future infrastructure should be optimised for occupancy (“less is more”) and built with resilience in mind. This means building and retrofitting infrastructure to accommodate unforeseen circumstances like social distancing, while still fostering the collaborative environments that make cities centres of innovation. For physical infrastructure, this could mean adding modular features that make spaces more dynamic. Many streets in New York City, for example, now moonlight as areas for socialisation to limit the spread of COVID-19. On the digital infrastructure side, smart city technology could prove useful for contact tracing and other disease prevention efforts.

- Public transportation will need an overhaul that improves efficiency while limiting the spread of disease. Diversifying public transport methods and building out services like water taxis can be a part of the solution, while upgrades like open gangways on subways can increase space by up to 10%.6 Additionally, the Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence can optimise how public transit runs to limit capacity and enable distancing.

- At the beginning of the pandemic, stay-at-home orders meant that large portions of the labour force relied on cloud computing technology to work from home. Though offices are reopening their doors, the success of the work-from-home experiment means that businesses are more open to flexible work arrangements than in the past. Companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Slack, for example, now have indefinite remote work policies. Additionally, areas that lacked digital infrastructure suffered economically during the pandemic and increased digital infrastructure is essential to avoiding such disadvantages moving forward. As demand for cloud resources continues to rise, the oft-forgot back-end networks of digital infrastructure and hardware that enable cloud computing will have to scale in lockstep.

What Does a Biden Administration Mean for Infrastructure Development?

U.S. President Joe Biden ran on a platform that featured aggressive infrastructure investment as a key pillar of economic policy and potential COVID-19 recovery efforts. In March, these plans became clearer in the form of the American Jobs Plan, which outlined key areas of infrastructure the Biden Administration hopes to see of investment across. Much of the plan is covered by the below:7

Physical Infrastructure

Transportation: The American Jobs Plan seeks to improve transportation infrastructure through investment across roads and bridges; public transit; electric vehicles (EV); passenger and freight rail services; and ports, waterways, and airports. Notable goals include building and repairing 20,000 miles of highways and roads, establishing and building a U.S. electric vehicle market, and upgrading commerce-facilitating infrastructure like railways, ports and waterways, and airports.

Buildings, Schools, and Hospitals: Other efforts to revitalize physical infrastructure encompass funding for commercial buildings, homes, schools, and hospitals. In particular, the plan seeks to build and retrofit over 2 million energy-efficient electrified buildings and improve education infrastructure by modernizing schools and college.

Infrastructure Resilience: President Biden’s plan highlights the importance of ensuring that existing and new infrastructure is resilient to climate risk, natural deterioration, and obsolescence. Investment areas in this vein include protection from wildfires, coastal resilience, and research and development in durable advanced materials.

Energy, Water, and Digital Infrastructure

CleanTech and Clean Energy: The Plan specifies investment in expanding electrification and energy efficiency in buildings, homes, schools, and hospitals, as well as in electric vehicles. The plan highlights President Biden’s intention to catch up with the rest of the world by achieving 100% carbon free electricity by 2035 and putting the country on a path to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Water utilities: The plan includes a significant overhaul of the U.S. water utility infrastructure to improve the safety of drinking water. It seeks to invest in replacing 100% of all lead pipes and service lines that deliver drinking water and upgrading treatment plants and systems.

Digital infrastructure: The plan also seeks to expand internet infrastructure, covering 100% of the country with high-speed and future-proof broadband.

How Close is the U.S. to Making Infrastructure Investment a Reality?

Infrastructure dominated the national conversation in the U.S. since President Biden outlined the American Jobs Plan in March. In August 2021, the U.S. Senate passed the US$1.2T Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act across bipartisan lines, after months of deliberation. The bipartisan bill features US$550B of new spending across transportation and transit, clean technologies, water infrastructure, digital infrastructure, and infrastructure resilience, with remaining spending coming from existing infrastructure funds and repurposed funds from other areas. The bill is part 1 of 2 pieces of potential legislation drafted in the spirit of President Biden’s physical and social infrastructure agenda as articulated by the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan. Part 2 of this agenda could come in the form of a partisan US$3.5T budget reconciliation bill, which would invest in education, affordable housing, clean energy, and health care, among other areas. A preliminary budget resolution that would allow such a bill to pass along single-party lines has already been adopted by both houses of Congress. As of the end of August, the Senate is drafting the reconciliation bill for a possible vote in late-September or October. Given this timeline, the House intends to vote on the bipartisan bill by September 27th at the latest, potentially meaning that President Biden could sign both, or least one, of the bills into law in the coming months.

The sum of new spending across the resolution and bipartisan bill pares in comparison to the combined US$4.1T number from the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan announced in March/April. Progressive Democrats in the House might be irked by this, but in our view, the spending outlined in the spring was higher than what is realistic in order to accommodate negotiations and compromise. We are encouraged by the significant funding appropriated for clean energy in the reconciliation bill and also expect hundreds of billions of dollars invested in affordable housing, education, and health care to go toward additional physical infrastructure in the form of buildings and clean technologies.

Issues in Approaching Infrastructure Investing

Many approaches to investing in infrastructure tend to focus on the owners and operators of existing infrastructure assets, rather than on the companies that derive a significant portion of their revenues for building or maintaining infrastructure assets.

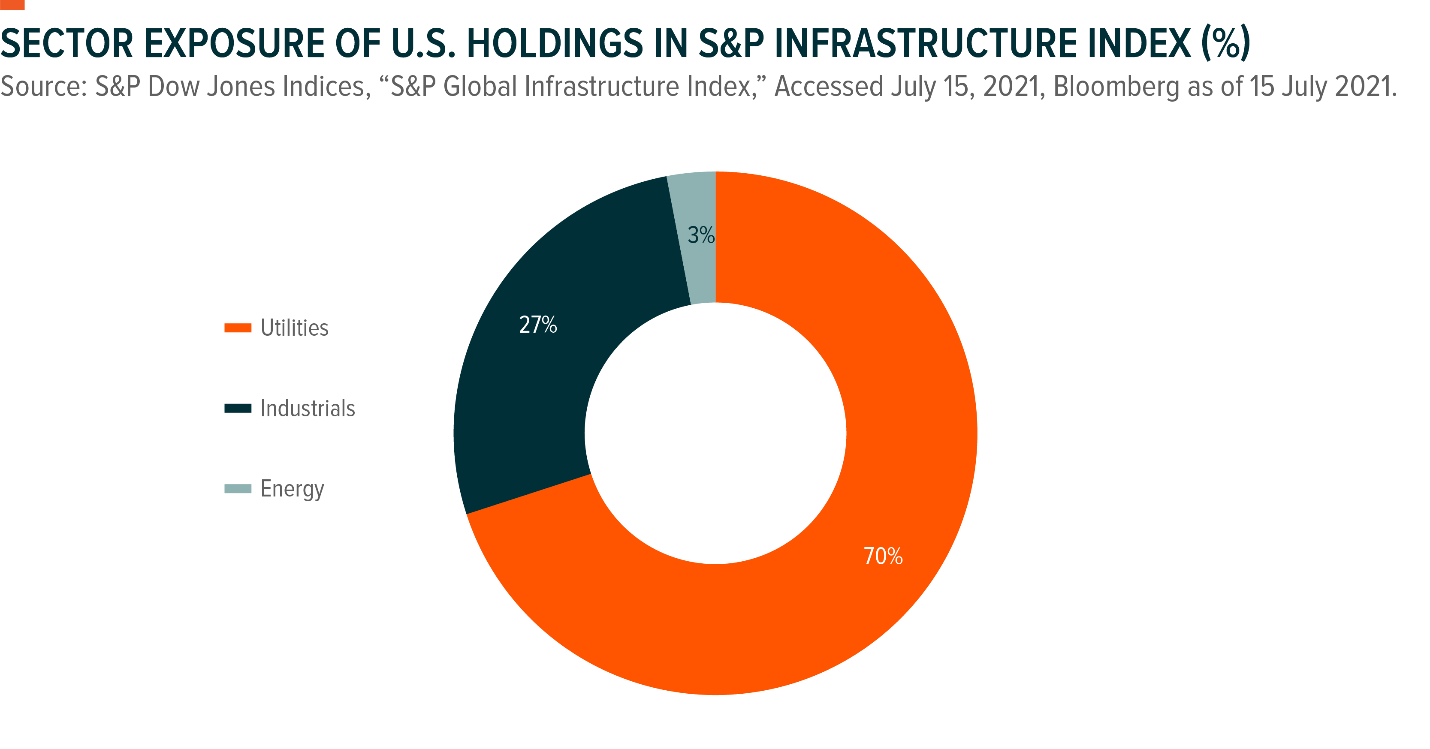

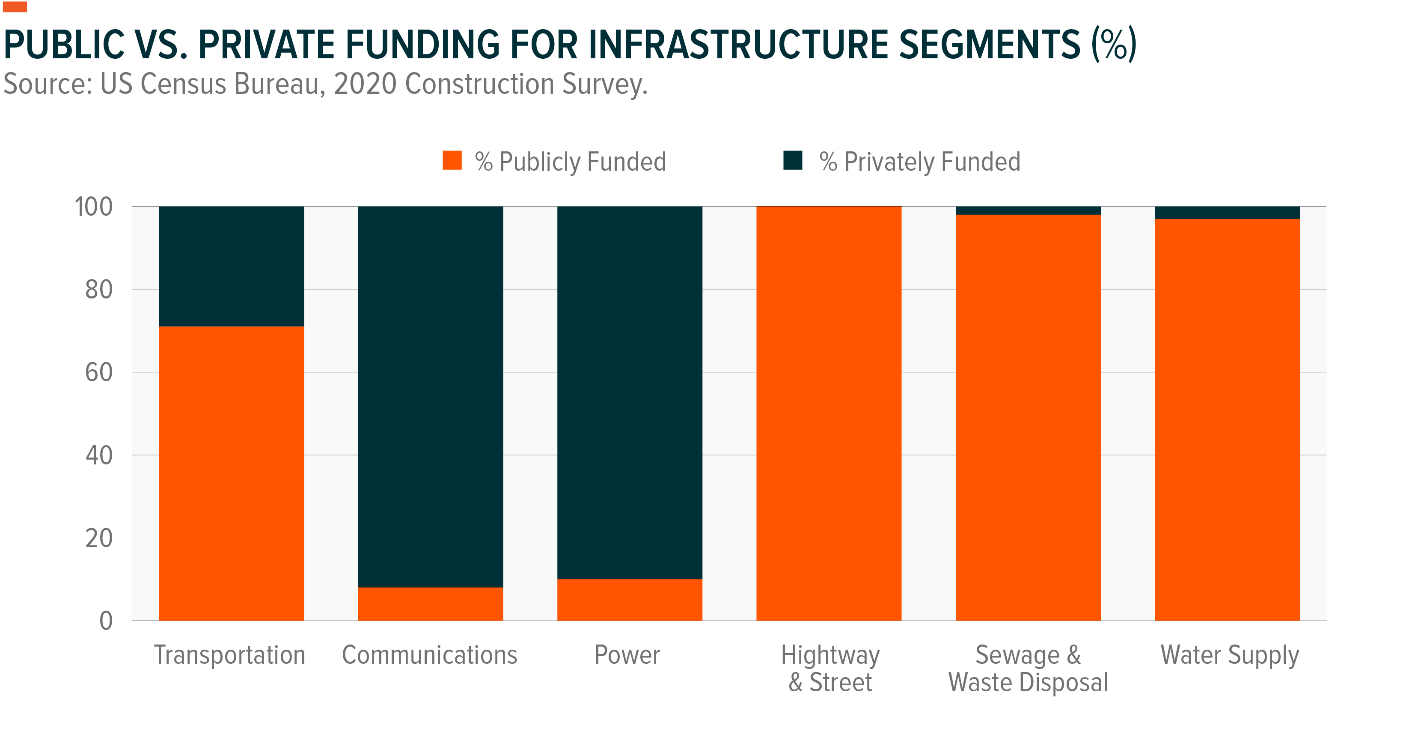

For example, 90% of the US components of S&P Global Infrastructure Index are utilities and energy companies that operate infrastructure assets.8 While these companies do make investments to maintain and develop infrastructure, they potentially stand to benefit from only a minor portion of total infrastructure spending in the US. In 2016, these firms were responsible for one-third of total infrastructure spending in the US.9 In addition, 40% of these firms’ infrastructure spending was not an investment in new infrastructure, but an expense to maintain existing assets.10 Therefore, no additional cash flows are expected to be derived from that portion of their infrastructure spending. When considering the portion of funds that are channelled towards building new infrastructure assets, additional revenue from these projects could still take years to materialise.

Given the concentration of publicly traded infrastructure companies in the Utilities and Energy sectors, much of their investment is concentrated in only a few segments of infrastructure. Therefore, companies in these sectors do not participate in a significant portion of infrastructure development, such as building roads, bridges, and water infrastructure.

Conclusion

Entering 2020, we anticipated that the Presidential election would feature infrastructure development as a key topic. The COVID-19 pandemic ensured it did not quite pan out that way. But this does not mean infrastructure investment is any less necessary or imminent. In fact, we believe the events of 2020 reinforce the case for infrastructure development and will shape what the next generation of US infrastructure will look like. Further, President Biden’s approval of the bipartisan infrastructure deal is the closest the U.S. has come to sweeping infrastructure spending in recent history. If passed into law, the deal would represent the largest infrastructure package ever enacted in the United States. In our view, such spending will translate to revenues for companies involved in infrastructure development and that derive a significant share of their revenues from the U.S.

This document is not intended to be, or does not constitute, investment research