Using a Thematic Approach to Invest in the Digital Economy

We are living amid the Fourth Industrial Revolution which is the digital transformation of the global economy and societies. Digitisation has been a major driver of changes throughout the value chain. In this paper, we investigate the implications of the rise of the Digital Economy and explain how thematic investing can prepare investors for these disruptive changes.

The digital revolution truly started in the 1980s with the start of the Internet which provided computers the needed path to connect. Connectivity drove digitalisation. In the following decades, it accelerated further with the adoption of digital technologies proliferating across numerous industries, like manufacturing, banking, health care, and entertainment. Most recently, the global COVID-19 pandemic quickened the adoption of teleconferencing and distance learning technologies, as businesses and individuals adapted to stay-at-home orders. Like the creation of the steam engine, the electricity generator, or the printing press, the innovations which constitute the digital revolution (the computer, the Internet, automation, artificial intelligence, etc.) permanently and profoundly changed the way we operate in our day-to-day life.

Defining the Digital Economy

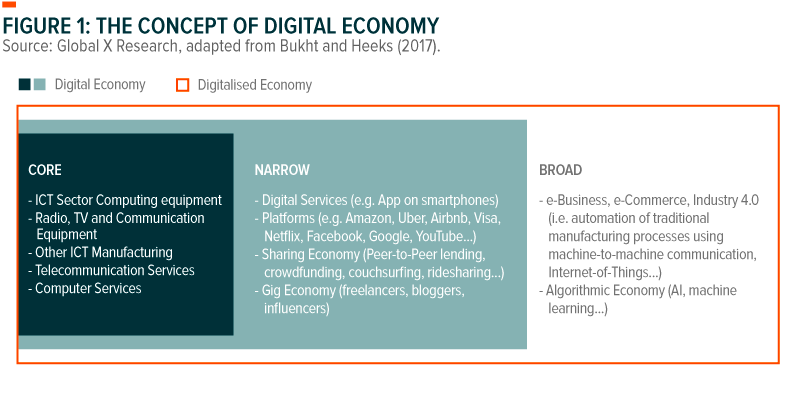

While there is no consensus of what encompasses the Digital Economy, it generally refers to all economic activity reliant or enhanced by digital inputs (i.e. Information and Communication Technology (ICT), digital infrastructure, products, services, and data)1. Some definitions are wider. For instance, the OECD describes the Digital Economy as “extending beyond businesses and markets as it includes individuals, communities and societies”.

Bukht and Heeks (2017) conceptualise the digital world as a tier system. They define the Digital Economy by “core” (i.e. ICT sectors) and “narrow” (including the economic activities reliant on digital inputs) measures, and differentiate the Digital Economy from the broader digitalised economy which includes economic activities that are enhanced by digital inputs. The authors describe the Digital society as all the other digitalised activities not included in the GDP.

To what extent does the digital economy contribute to the overall economy?

Measuring the size of the Digital Economy as well as the extent to which it contributes to overall economic growth is challenging since digital inputs are incorporated throughout the global value chain. To overcome this challenge, the G20 countries are working on the elaboration of a standardised digital satellite account, while the OECD founded a working group dedicated to developing new classifications and accounting metrics to better reflect digital reality in GDP measure2. Meanwhile, most national statistics define the Digital Economy as only the ICT sectors, which likely underestimates the true size and economic impacts of the Digital Economy.

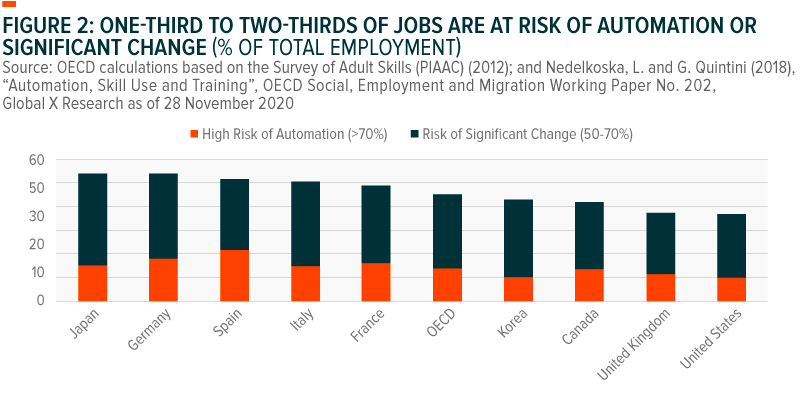

Overall, the core measure of the Digital Economy (i.e. ICT sector) currently represents about 5% of the global GDP and 3% of global employment. However, the digitalised economy generated almost half of value added and half of the new employment in G20 economies between 2006 and 2017, according to OECD’s estimates. Its size is smaller in developing nations where it represents approximately a quarter of total employment. The digital transformation is expected to increase productivity over the long-term, lower prices, boost demand for new innovative products and ultimately create jobs in digitalised sectors. In contrast, sectors of low digital-intensity may experience more job destructions because of automation rather than digitally intensive sectors (figure 2).

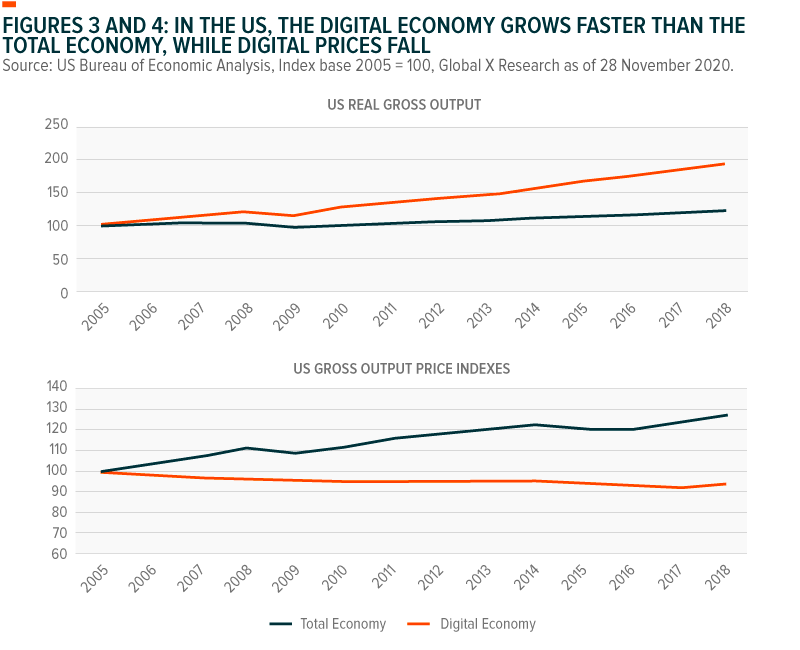

In the US, the Digital Economy accounted for 9% of GDP in 2018 and grew at an average annual rate of 6.9% from 2005 to 2018, compared to just 1.7% annual growth for the total economy over the same period3 (figure 3). Despite the relatively small size of the Digital Economy, it accounted for 20% of the total 2.9% growth in real GDP in 2018 and 6% of the total US employment in 2018. Interestingly, the prices of digital goods and services have been declining by 0.5% per year in average since 2005, while US inflation rate remained close to 2% annual (figure 4). In 1971, storing 1 GB of data would have cost approximately US$250 million, compared to less than US$0.03 today. The declining costs of digital inputs likely results from multiple factors including the continuous improvements in technology reducing the cost of productions as described by Moore’s Law4, economies of scale due to rising production and demand for technology goods and services, and increased competition in the ICT sectors.

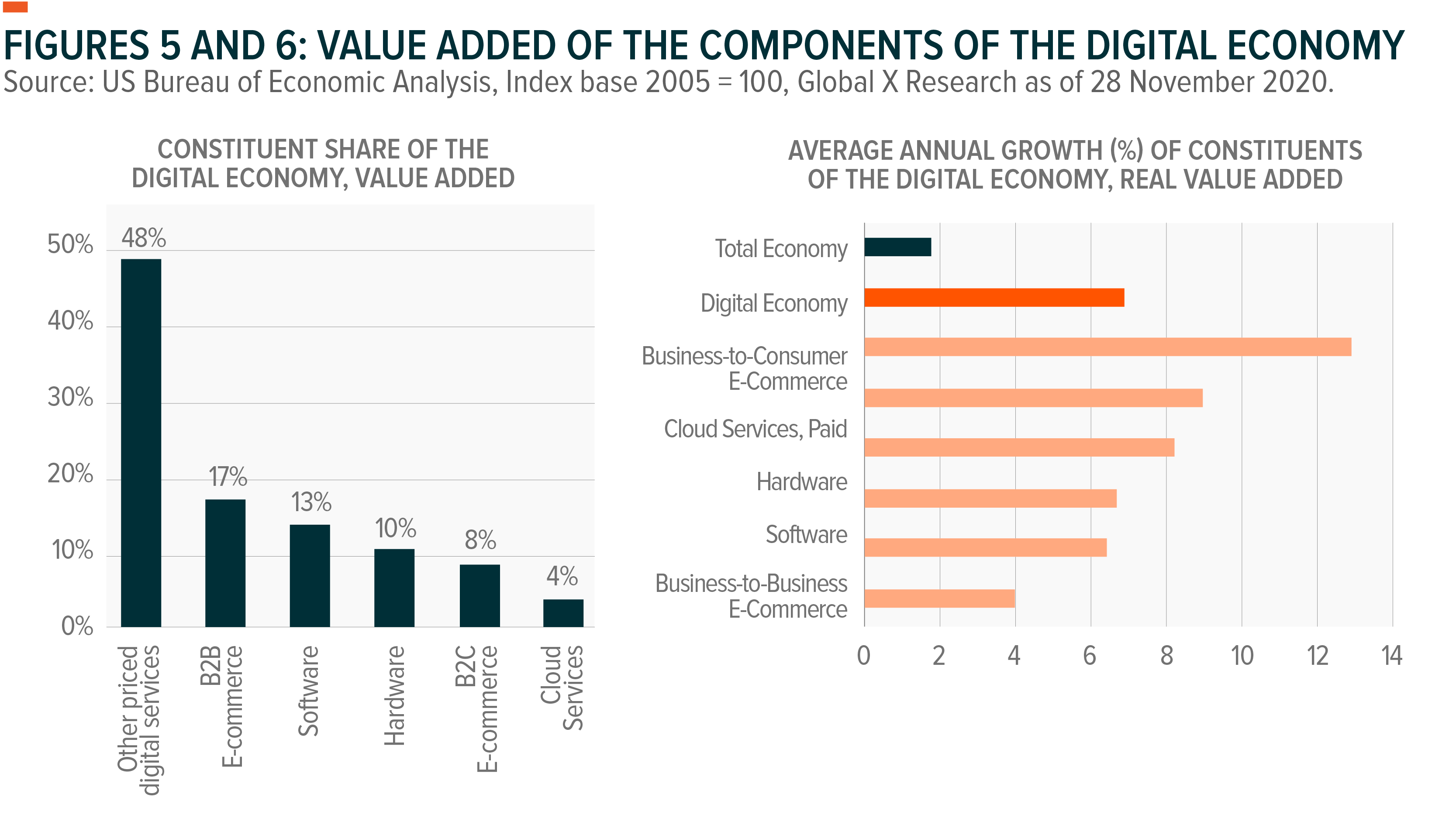

Typically, the digital inputs have been predominantly used in services-producing industries (90%) compared to the goods-producing industries (10%) (figure 5). E-commerce business-to-consumer (B2C) activities and cloud services have been growing the fastest among all components of the Digital Economy (figure 6). However, with the rising automation of industrial processes, the contribution of the digital inputs to the value added in the production of goods is likely to increase rapidly.

The race to global dominance in the Digital Economy

The adoption of digital technologies is heterogenic across industries and countries, with rising disparities in terms of digital infrastructures, skills, regulations, and social preferences, and resulting in a fragmented Digital Economy. Most technology companies are in the US and Asia, while Europe captures only 10% of global funding for its start-ups5. Technology has been a rising source of geopolitical tensions within western countries and between the US and China in the past few years. In response, international cooperation on digital technologies are emerging among western nations. The victory of Joe Biden in the US presidential election revived talks around a transatlantic agenda between the US and the EU which encompasses policy proposals of the digital environment, including common approaches to antitrust enforcement and cybersecurity6. This agenda underlines the determination of the EU and US to shape the digital regulatory environment.

To mitigate the economic and social disruptions resulting from the digital transformation, governments are setting new digital policies. For instance, the European Commission (EC) announced a Digital Single Market strategy in 2015 and renewed its commitment to digital in its EU Next Generation Recovery Plan unveiled in May 2020 in response to the global coronavirus pandemic. Since 2015, the European Union strengthened the digital legal framework by establishing specific regulations on the platform economy, rules for artificial intelligence (AI) and crowdfunding. The EC also launched targeted programmes to promote the digital transformation more evenly across the region, supporting fast and free internet connections (including 5G), authorising streaming across borders, and facilitating cloud computing, among other digital initiatives. These programmes are aimed at increasing growth and productivity through the integration of digital inputs across all sectors and particularly encourage small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to participate actively in the digital transformation in sectors of typically low digital intensity. For instance, the EU funded a Data Driven Bioeconomy project in 2017 which aggregated big data from the agriculture, forestry, and fishery industries and use intelligent processes to analyse and visualise data on harvests, seeds, and use of fertilisers. This project has helped reducing spraying and irrigation costs by 30% for European farmers, according to the EC.

The increasing regulation and international cooperation to create new standards for the Digital Economy would enable and support the adoption of technology globally, and potentially lessen the adverse consequences of the digital transformation through adequate policies around education and international mobility of workers. Meanwhile, the geopolitical tensions are likely to continue amid the innovation race dominated by the US and China for the global leadership in the Digital Economy.

The digital transformation of business models, moving towards Industry 4.0

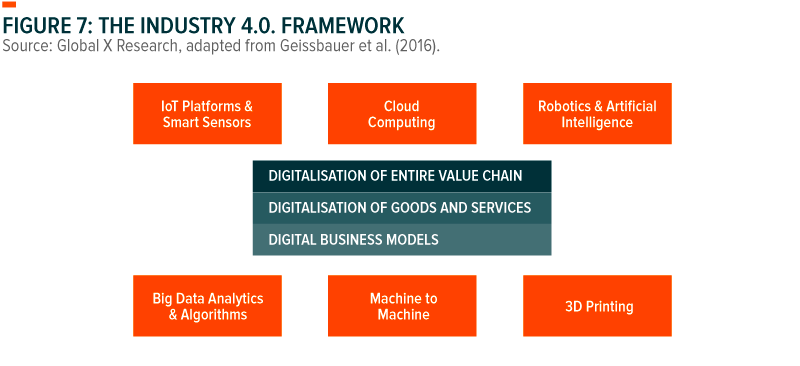

Digital innovations are transforming the entire ecosystem. New business models emerge across all services from entertainment to finance with subscription models (e.g. Netflix), free models (e.g. Instagram, Facebook, etc), on-demand models (e.g. Uber), or sharing models (e.g. AirBnB) to name a few. Similarly, the adoption of cyber-physical production systems has accelerated the pace of the digital transformation of manufacturing and industrial processes since the 2010s, resulting in the “Industry 4.0” or the Fourth Industrial Revolution7,8. Overall, the Industry 4.0 is characterised by implementing digital technologies across the production value chain. This new digital industrial framework encompasses the current trends of automation, the internet of things (IoT), cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. Today, software can substitute engineers to create certain machines. For example, additive manufacturing uses 3D printers to produce complex products faster and at lower cost than traditional manufacturing. Technology companies are transforming the traditional manufacturing business model by incorporating data-analytics to hardware, leading to the emergence of IoT business models like predictive maintenance and outcome-based business models selling and pricing performance instead of hardware9. The hardware-focused business model in manufacturing is shifting towards a broader business model including hardware, software and services, blurring the line between traditional sectors.

Capturing the Potential of the Digital Economy

The disruptive nature of the digitalised economy challenges traditional investment frameworks. Conventional portfolio construction is often structured around managing traditional sector allocations relative to a benchmark to generate excess returns or reduce risks. Traditional sectors, however, are already well-established segments of the economy and tilt heavily towards the companies who have been historically successful. Conversely, companies leading in disruptive themes, like those that implement the IoT in to enhance the manufacturing process, are often smaller in nature and can range across different sectors and geographies. Accurately capturing these firms therefore requires a forward-looking investment approach that extends beyond the traditional sector frameworks to identify the fast-growing trends of the next decade.

Thematic investing is an investment approach which involves in-depth research to identify the disruptive trends that will drive of value creation in the future, and the companies best positioned to benefit from the materialisation of these trends. Thematic ETFs can help investors gain targeted exposure to these disruptive themes in a single investment. They use a systematic investment process to assemble baskets of securities that provide distinctive and diversified exposure to certain disruptive themes like the IoT, Robotics and AI, Video Games and Esports, or Telemedicine and Digital Health. In order to accurately target these disruptions, thematic ETFs should only include specialist companies that have the most to gain from the emergence of these themes. One way of constructing a pure-play portfolio is to select companies having most of their revenues generated by activities directly linked to the targeted disruptive theme. Therefore, thematic investing is a growth-oriented strategy which not only has the potential to outperform over the long term, but also constitute unique building blocks to prepare global equity portfolios for an increasingly digitalised world.

This document is not intended to be, or does not constitute, investment research